REDISCOVERY

ANTIQUITY IN MODERN ADVERTISING

This section will focus on why antiquity, particularly from Greek, Roman and Egyptian cultures, remains a popular theme in modern cosmetics. To fully understand the appeal of ancient imagery and motifs in makeup packaging and advertising, it is necessary to examine 1. why they are used across many seemingly disparate categories of design and consumer goods, and 2. why they make an especially fitting choice for marketing cosmetics.

This is not to say that ancient iconography from cultures outside of the three mentioned does not exist in cosmetics, but it does indicate the dominance of these civilizations in the Western imagination. Greek and Roman sculpture and architecture were considered to represent the pinnacle of artistic achievement during the Renaissance and Neo-Classical eras, and artists reflected this reverence by incorporating elements from ancient Greece and Rome into their work. The repeated plundering of historic Egyptian sites led to European and American appropriation of their culture, most notably after Napoleon’s Egyptian campaign and the opening of King Tutankhamun’s tomb. In short, the high esteem in which ancient Greek, Roman and Egyptian cultures were held in Western eyes led to their being referenced more so than other cultures, making them easily recognizable across diverse audiences over time. This familiarity in turn made them prime candidates for marketing any number of products. As Lauren Talalay explains: “Each of these three ancient societies has been necessarily reduced to a prescriptive shorthand that belies the complexity of the cultures. The exotic is appropriated from Egypt, the cultured from Greece and the technical ingenuity from Rome. Reducing the cultures to stereotypes helps cast the civilizations as both intriguing but not too alien, and accessible but not too familiar…ad designers need ‘totemic’ images and highly condensed visual vocabularies that maintain the worlds of archaeology and antiquity as static and essentialized entities.”(1) Examples of these principles abound in the cosmetic world. DeFleury’s Vanipact powder case directly references the Neo-Classical appetite for ancient Greek and Roman art by replicating Antonio Canova’s 1793 sculpture Psyche Revived by Cupid’s Kiss. Even companies outside the Western world recognize the potency of ancient Greco-Roman and Egyptian imagery. Historic Japanese brand Shiseido used illustrations of Greek and Roman goddesses in their early advertising, while fellow Japanese company Kanebo embossed their Milano face powders with similar figures.

Additionally, the depiction of marble statues and architecture in ads and the use of gold in both packaging and makeup shades that reference antiquity convey status and luxury. Deborah Lippmann’s Nefertiti nail polish (2009) is an opulent golden hue, and Beautaniq’s Golden Goddess palette is adorned with illustrations of marble statues and consists of rich metallic shades. Advertising’s inclusion of costly materials frequently used in ancient art and architecture heighten the attractiveness of modern products by implying the buyer is cultured and refined. This is especially true in ads that define classic designs or products through the inclusion of ancient artifacts and structures. A 1945 ad by Volupté highlights the “classic elegance” of their compacts by showing a krater in the background, while Helena Rubinstein’s 1940 ad for “classic” lipstick shades presents them in cases resembling Greek columns. Using ancient motifs as signifiers of good taste and affluence also helped mitigate the perception of makeup, and its wearers, as gauche or low-class, a common sentiment in first half of the 20th century.

LINKING PAST AND PRESENT

The use of ancient Greek, Roman and Egyptian civilizations in advertising for basically every category of consumer goods is well-documented and easily explained. But why is this tactic especially relevant for cosmetics? First, the deployment of antiquity in makeup advertising and collections provides consumers with a way to both maintain and rejuvenate ancient cosmetic traditions. Humans, particularly women, have been wearing makeup for millennia. Ads and collections that center antiquity encourage participation in an age-old practice, but in a thoroughly modern way. Beauty customs are presented as being passed down through millennia, traditions that today’s women can still partake in through the use of modern makeup. Palmolive’s 1920 “Re-incarnation of Beauty” ad depicts a mummy case of a pharaoh placed directly behind a woman in contemporary dress, while the copy states that ancient Egyptian princesses “bequeathed a heritage of beauty to the modern girl.” A 1956 ad for Elizabeth Arden’s eye kohl declares that it’s “a superfine powder as ancient as the Sphinx, yet new as tomorrow on wide Western eyes!” A year later, Lancome featured the “two faces of Venus” in a makeup ad, demonstrating that busy modern-day goddesses can now easily achieve beauty both day and night.

Lancome ad, 1957. Purchased from hprints.com

Further, cosmetic companies seized on the fascination with beauty history and its artifacts (Roman skin cream jars, Egyptian kohl containers, etc.) by presenting their products as a latter-day version of what ancient beauties wore. By using certain items, the modern woman can achieve the same beauty as ancient goddesses and queens despite the temporal distance. In some cases, references to antiquity are used to demonstrate the superiority of today’s beauty offerings. While the ancients may have defined classic beauty, makeup advertising asserts contemporary women have a much easier time achieving these ideals by using new products. “Think your preparty ritual of bath oil, eye make-up, perfume and hair glitter is something new? It’s been going on for untold milenniums! [Egyptian] ladies used eye shadow, lip rouge, cheek rouge, nail coloring and hair cosmetics and perfumed oil. Naturally these damsels from the land of the Nile didn’t enjoy the same assortment and refinement of cosmetics that we do,” states a column in Seventeen magazine.(2) “Cleopatra would have given her crown for your make-up,” announces a 1954 headline, noting that the queen “would have swapped us a kingdom for a supply of our make-up, but instead had to content herself with the cruder cosmetics of her time.”(3) A 1939 ad for Tattoo lipstick takes the idea a step further, claiming that women today could actually be even more seductive than Cleopatra herself. “Cleopatra would probably have added a couple more Emperors or so to her bag – if she had known about real glamour – Tattoo glamour! Tattoo wasn’t discovered in those days, but of course if she had lived today she would have used Tattoo.”(4) Cosmetic companies also use female figures from antiquity to underscore the notion of “timeless” beauty that is impervious to trends, i.e. an ideal that never goes out of style. An article at Dazed Beauty discusses the power of the “timeless vision of female beauty” embodied by the famous bust of Nefertiti and referenced by various cultural icons such as Rihanna and Iman. “It’s looking back through the centuries at a woman living in wildly different circumstances who used beauty in the same way we do today: to communicate publicly who we are, to express our uniqueness, or as a protective, even talismanic layer. Beneath the specifics of her make-up regime and aesthetic preferences, it seems that even ancient Egyptian queens were just like us.” In this way, the beauty of the ancients becomes relatable and attainable for today’s women.

This idea is fully realized in Lancôme’s fall 2023 collection, the ad campaign for which linked four of the company’s celebrity ambassadors with figures from antiquity by photographing them alongside sculptures of their respective muses or goddesses from the Louvre’s collection: American actress and singer Zendaya is shown with Winged Victory of Samothrace; Chinese actress He Cong with the Venus de Milo; French singer Aya Nakamura with a bust of the Greek poetess Corine; and American actress Amanda Seyfried with Diana of Gabii. The packaging also demonstrates the previously discussed tactic of alluding to luxury and worldly sophistication by using images of the museum’s marble sculptures of these mythological figures and others from the Louvre’s collection.

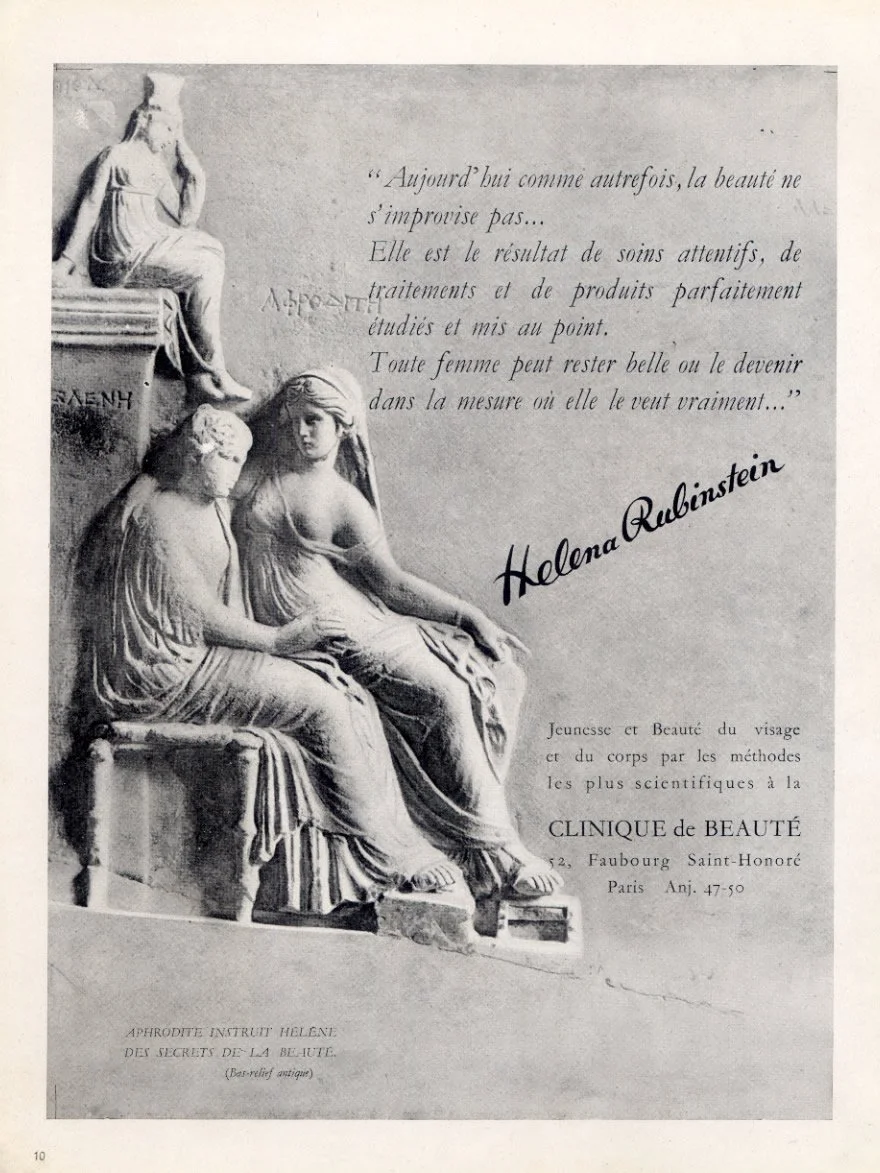

Secondly, the divulging of (presumably) ancient beauty secrets is exciting in a way that’s different from other techniques used for marketing cosmetics. Unlike, for example, advice offered by celebrity makeup artists, a link to legendary beauties (who, arguably, were celebrities of their time) places the consumer right alongside them and makes them feel as though they’re receiving exclusive information. Armed with knowledge that was obscured until now, women are able to recreate the allure of Cleopatra and others thanks to cosmetic companies’ willingness to share. Two 1923 ads for Kiija, a liquid powder produced by the Tokalon company, read “Le sphinx a parlé” (“the sphinx has spoken”) and “La clé d’un mystere (“the key to a mystery”) and allude to ancient beauty wisdom that has finally been disclosed.(5) Another Kijja ad states that Cleopatra was the “greatest enchantress of all time”, yet still did not meet conventional beauty standards: “Contrary to general opinion, Cleopatra was by no means what might be called a perfect type of beauty;” but “knew how to make the most of her charms in order to appear always at her best – which most women do not know.” This ad and others suggest that Cleopatra was heavily aided by both cosmetics and the knowledge of applying them to her advantage: “The fact is, Cleopatra was no beauty. But she sure knew how to get the guys. Cleo’s secret: makeup.”(6) An ad for Helena Rubinstein skincare continues the theme in its usage of a 1st century B.C.E. bas relief with two seated women representing Aphrodite and Helen of Troy, which the company interpreted as the goddess giving beauty tips to Helen. In this way cosmetics companies present themselves as historical experts with insider information that only they have the authority to impart.

Helena Rubinstein ad, 1946. Purchased from hprints.com

Antiquity in makeup ads was also utilized to tout the latest styles and colors. A 1941 Revlon ad shows a model sporting bright red nails and lipstick and declares “you, too, can be a modern goddess” through the purchase of their new shades. Harper’s Bazaar invoked the goddess Diana to feature Germaine Monteil’s spring collection in their April 1964 issue: “Diana, goddess of the moon, and of the hunt, celebrates the natural and free spirit. Her panther grace, her special affinity for all outdoors, suggests this new color scheme for eyes and mouth – green eye shadow, blended with moonlit glimmers of gold and beige, and a lipstick triumphantly pink. Germaine Monteil calls this color Navy Pink Day – the counterpoint to Cat’s Eye green shadow – both from her Pace Setter collection.”(7)

Finally, the idea of magical ability to transform from average mortal to bewitching divine being or powerful queen through the use of cosmetics is another appealing aspect of antiquity-themed makeup ads and collections. Beauty products associated with goddesses whose abilities transcended the earthly realm or rulers who presided over empires allow the wearer of these products to imagine they wield the same powers as these figures, becoming more confident as a result. An ad for Estée Lauder’s spring 1992 collection was intended to bring out the “goddess in every woman,” while the ad copy for Uoma Beauty’s 2022 Salute to the Sun collection instructs the customer to “unleash your inner goddess”. A 2003 article about the goddess trend in fashion and pop culture notes that companies’ references to goddesses and their inherent beauty speaks to women’s desire to be revered. “Goddess worship has been around longer than anyone can remember, from the Venus of Willendorf to Marilyn Monroe to New Age feminists looking for alternatives to a patriarchal religion -- but for many women her newest face is about worshipping yourself…The idea plays well into modern women’s struggles with body issues. Rather than run from it, retailers are using the trend to their advantage: Passion, the new pink Venus razor from Gillette, ‘makes it easy for every goddess to reveal her beauty.’” A 1959 ad for Germaine Monteil’s eye makeup, which shows an illustration of a Nefertiti-esque bust, suggests that using their new products will inspire idol-like worship of the wearer. The colors of Helena Rubinstein’s 1969 Mykonos collection provided “sorceress eyes” and conferred queenly status: “they’ll think you married Croeseus.”

Germaine Monteil ad, 1959. Purchased from hprints.com

“Egyptian eye” styles in particular connote strength authority given their association with Egyptian rulers. The West viewed the heavy, graphic black eyeliner tradition as seen on ancient sarcophagi of the pharaohs and the bust of Nefertiti as both emblematic of royalty and visually striking. From Theda Bara’s and Elizabeth Taylor’s respective film roles as Cleopatra to Rihanna’s portrayal as Nefertiti on the April 2017 cover of Vogue Arabia, Egyptian eye makeup became connected in the Western popular imagination with drama and power. Although members of all social strata in ancient Egypt wore substantial black eye makeup for medicinal or religious purposes, malachite and other colorful mineral pigments favored by the ruling class resulted in some modern re-imaginings of the Egyptian eye as a combination of bold hues alongside black. The use of color strengthened the notion of Egyptian eye makeup styles as daring and commanding attention.

CONCLUSION: TIMELESS BEAUTY

The expression and redefinition of classic beauty ideals via images of antiquity demonstrate their ability to simultaneously maintain harmful notions of beauty and act as a tool to challenge them. The deployment of ancient themes fosters a deeper understanding of makeup history and artistry as a whole, and forces consumers to confront the more problematic aspects of the cosmetics industry. More generally, it contributes to increased awareness of cultural appropriation but also appreciation for ancient history and art, and presents an opportunity to promote ancient civilizations beyond Greece, Rome and Egypt or lesser known stories and figures within those cultures. Moreover, by linking makeup to less commonly used myths and characters and showing a variety of races, ages and genders, cosmetic advertising that centers antiquity contributes towards more progressive and inclusive notions of beauty.